Social Studies Skills

No matter the content area or question format, GED social studies questions assess one of three skills:

- Reading for meaning,

- Analyzing Historical Events and Arguments

- Using Numbers and Graphs

Reading for Meaning

Reading for meaning means that you can:

- Determine a stimulus’ main idea

- Use details to make inferences

You’re likely to see these questions when the GED gives you a primary or secondary source to read. A primary source (e.g., a letter written by a soldier during war, a political cartoon) was written in the past and is about an event that happened around that time. A secondary source (e.g., a textbook) is a passage written about a past event where the author was not present.

Let’s look at a primary source, find its main idea, and make some inferences.

The following excerpt is from The Gettysburg Address, delivered by President Abraham Lincoln on November 19, 1863, in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.

But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate — we can not consecrate — we can not hallow — this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us — that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion — that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain — that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom — and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

Note

Before reading the passage, read the introduction. It provides you with the author, time, and place. Your knowledge of history, such as the Civil War and the Battle of Gettysburg, will play a role in finding the main idea and making inferences.

So, what is the main idea? In an excerpt, the main idea is likely within the first 1-2 sentences. President Lincoln writes that the Union soldier who died in battle have “hallowed” (i.e., made holy) the ground where he is giving his speech. He further emphasizes this point in sentence 2 by saying that the living have “poor power” (i.e., no ability) to achieve more than what these brave soldiers have done by giving up their lives. The rest of the speech reinforces these points.

What about inferences – conclusions we can draw based on evidence in the text? One way to find inferences is to ask yourself, “What message is the author trying to send?” Let’s look at the excerpt’s final sentence one more time:

that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain — that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom — and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

One potential answer is that, “Despite the Union losing many troops in the Battle of Gettysburg, President Lincoln vowed to press on and preserve the Union at all costs.” This is an inference, one that history proved correct, as President Lincoln led the Union to victory in 1865.

Analyzing Historical Events and Arguments

Analyzing historical events and arguments means that you can:

- Draw inferences based on the information presented and your knowledge of history

- Tell facts apart from opinions

Succeeding with this skill requires more social studies content knowledge than the other two skills. As a result, you’ll need to master the social studies content later in this guide if you hope to excel in answering these questions.

Instead of a stimulus, the question may present a brief paragraph describing something about one of the GED social studies test’s four content areas. Let’s look at an example and see if we can draw an inference before telling apart facts and opinions.

In the 1950s, African American civil rights activists began using civil disobedience to protest segregation. Like Rosa Parks, who refused to give up her seat on a Montgomery bus, they interfered with business operations by holding peaceful sit-ins at segregated lunch counters throughout the South. Many of these peaceful protesters experienced violence from white Americans who supported segregation. Many of these white people should have gone to jail. African Americans fought on, even though they knew they could lose their lives. The efforts of civil rights protesters led to major victories, such as greater access to the ballot and the end of legal segregation throughout the United States.

When we looked at a primary source document, we asked ourselves, “Why did the author write this?” When it comes to passages like this, we need to ask ourselves a different question: “What does this passage tell me about the ‘bigger picture’?” In this case, the ‘bigger picture’ is the American Civil Rights Movement.

Let’s focus on one sentence:

African Americans fought on, even though they knew they could lose their lives.

Think about what this sentence suggests about the resolve African American civil rights protesters must have had. Think about what it suggests about the conditions they were fighting to change. We can infer from this simple sentence that:

- African American civil rights protesters were extremely brave.

- The conditions of segregation had to be awful, as people were willing to put their lives on the line to put an end to it.

If you keep the ‘bigger picture’ in mind – and apply some of that content knowledge we’ll explore later on – you’re likely to excel with these kinds of questions. But what about telling apart facts from opinions?

As you likely know, opinions are a writer’s personal thoughts and feelings about their subject. Read the passage once again and see if you find the sentence that is opinion, rather than fact.

Find it? Here it is:

Many of these white people should have gone to jail.

We can tell this sentence is the author’s opinion in two ways:

- It breaks the flow of the author’s story about the Civil Rights Movement.

- Words like ‘should or ‘may’ mean the author is straying away from the facts.

Keep these two thoughts in mind as you separate facts from opinions on the GED social studies test.

Using Numbers and Graphs

Using numbers and graphs means that you can:

- Identify information in a chart or graph

- Interpret data presented in a chart or graph

- Draw conclusions or make predictions from a chart or graph

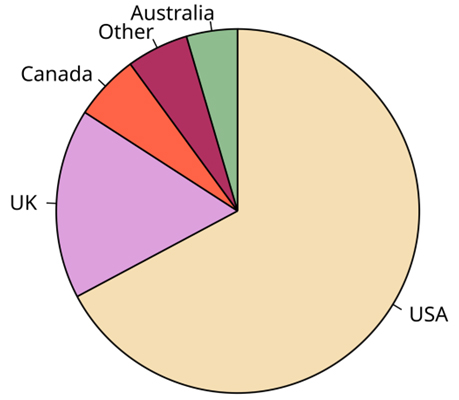

Let’s start with identifying information. Here’s a pie chart to get us started:

Population Distribution of Native English Speakers

Simple identification questions may include:

- Which country has the highest population of native English speakers?

- It’s the USA, which has the biggest slice of the pie chart.

- Which two countries have about the same number of native English speakers?

- They are Canada and Australia, which have slices that are about the same size.

Identification questions should take no more than a second or two to answer. Let’s look at one more example before moving on:

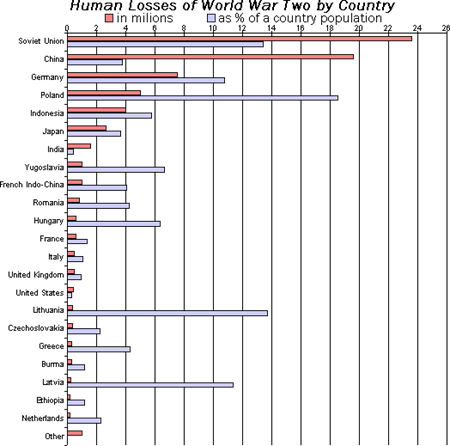

- Which nation experienced the highest death toll in World War II?

- The Soviet Union (just under 24 million deaths)

- Which nation lost the greatest percentage of its population in World War II?

- Poland (just over 18% of its population died in the war)

Because this chart measures two things, make sure to pay close attention to questions like those above. Even a simple identification question can trip you up if you’re not paying attention to what different-colored bars indicate.

Let’s move on to interpreting data presented in a chart or graph.

For now, we’ll stick with our World War II bar graph. Here’s an interpretation question for you to consider:

- What statement does the data in the table support?

- Lithuania and Latvia had relatively small prewar populations.

- The fiercest fighting took place in Germany.

- The United States and United Kingdom’s low death count helped them win the war.

- Greece surrendered quickly after being invaded by Germany.

In a question like this, each answer choice could be a true statement about World War II. Your goal is to find the statement the data supports. In this case, the first statement, “Lithuania and Latvia had relatively small prewar populations” is correct because they lost relatively few people but an overall large percentage of their prewar population. The graph’s data does not support the other answer choices.

Lastly, let’s focus on drawing conclusions or making predictions from a chart or graph.

This is an advanced skill, one where you’ll need consider each answer choice in light about what you know about U.S. history. Let’s consider the following question about our World War II bar graph:

- The data in the graph helps explain which action the superpowers took during Cold War?

- The United States landing Apollo 11 on the Moon

- The Soviet Union setting up communist governments in Eastern Europe

- The United States investing heavily in a federal highway system

- The Soviet Union sending nuclear warheads to communist Cuba

Again, just like in our previous questions, each of the answer choices could be true about the relationship between World War II deaths and the Cold War. In this case, each of these events happened. However, the data in the chart relates to only one statement:

- The Soviet Union setting up communist governments in Eastern Europe

The table tells us that the Soviet Union lost over 23 million people (i.e., about 13% of its prewar population) during WWII. This and the physical destruction the country experienced caused Soviet leader Joseph Stalin to create a “buffer zone” in Eastern Europe – reliable, friendly governments that would do the Soviet Union’s bidding. This decision led to the creation of the Soviet-backed Warsaw Pact in Eastern Europe and the U.S.-backed NATO in Western Europe.